Against Carceral Teaching: AI Edition

On ChatGPT in education, student punishment, & the value of doing stuff yourself.

One of my biggest pet peeves is when teachers have an adversarial relationship with their students. Phrases like “I had a rough education and so should you!”, “I’m making this class hard because that’s how the REAL WORLD is gonna be!”, “I don’t care if my students like me”, “you SHOULD be able to do this”, or “I already said that, you SHOULD have been listening” are everywhere in college instruction, especially the cut-throat world of STEM education. Engineering students are so damaged by this kind of relationship that they develop a Stockholm Syndrome-esque coping mechanism to deal with it, maladapting with mythical meritocracy rhetoric and internalizing the idea that STEM students must be superior (*blech*) to Arts student because they work in such a “rigorous” field. Some teachers pride themselves on how difficult their classes are, how low their exam averages are, and how many students are “weeded out” by their instructional methods.

But even if you’re a teacher who never use these phrases, preferring to treat your students with a bit more kindness, you may still be participating in another aspect of education that is as ubiquitous as it is harmful: the idea that when a student does something that the instructor considers “wrong”, that student must be punished.

That’s why when ChatGPT was released this past winter, educators everywhere threw a fit. Syllabus statements outright banning the use of the language learning model-based tool were written up by individual instructors, and in some cases mandated at the college level. Many instructors were reasonable, allowing for some use of the tool in the classroom, and some universities created stock syllabus statements for instructors who are for using the tool and those who are against the tool. Even with the tacit acceptance of ChatGPT, ever since its release there’s been an undercurrent of resentment about it.

I’ve criticized ChatGPT in the past, and I still think these criticisms are warranted. We cannot ignore the fact that tools like generative AI are only possible thanks to the invisibilized labor of marginalized groups both in the imperial core and the imperial periphery. In general, I believe the real problems with AI—worker exploitation, its demolition of media literacy, its potential for misinformation, and the broader capitalist system that incentivizes companies to fire human workers in favor of AI—are not talked about nearly enough. Instead, a different strand of tech-negative views are more common, focusing more on its unwelcome disruptions to the status quo:

“Students are just going to use it to cheat. They’re asking a chat bot to write their essays for them, which is plagiarism, and we should do whatever we can to stop that.”

This stance is more mainstream than you think, and I think it’s unproductive for two reasons. The first reason is that it doesn’t get to the main core of what AI tools are actually doing to the world of education, art, science, and more. The second reason is that it positions students as inherently bad actors that must be set straight with strict rules, which is a terrible way to think about your students. Allow me to explain using three examples of ChatGPT-assisted learning, and for simplicity’s sake, I’ll focus my thoughts on college essay-writing.

For the past several months, I’ve been working on a study with educators from across UMass about student motivations for using AI learning tools. Basically, we asked students around the college about how (and why) they’re using ChatGPT and related tools in the classroom, or if they’re not using them, why not? The study is not yet complete, and I don’t feel comfortable sharing any data with you all just yet; we’re taking our time to churn over this data, moving with a philosophy of “move slowly and fix things”, the antidote to Big Tech’s philosophy of “move fast and break things”. (That said, consider subscribing to this newsletter to get the study as soon as it drops; this newsletter is free!)

However, I will share one thing we figured out very quickly: very few students are using ChatGPT to generate full essays without thinking critically at all. Rather, many more students are using it (1) to edit their already-finished essays, (2) to flesh out a list of arguments and bullet points into a cohesive whole, or (3) to find facts or generate ideas for what they can use in their essays. We’ve indexed many more use-cases than this, but I think these three lay out a much broader picture than the perception that “students are using ChatGPT to cheat”.

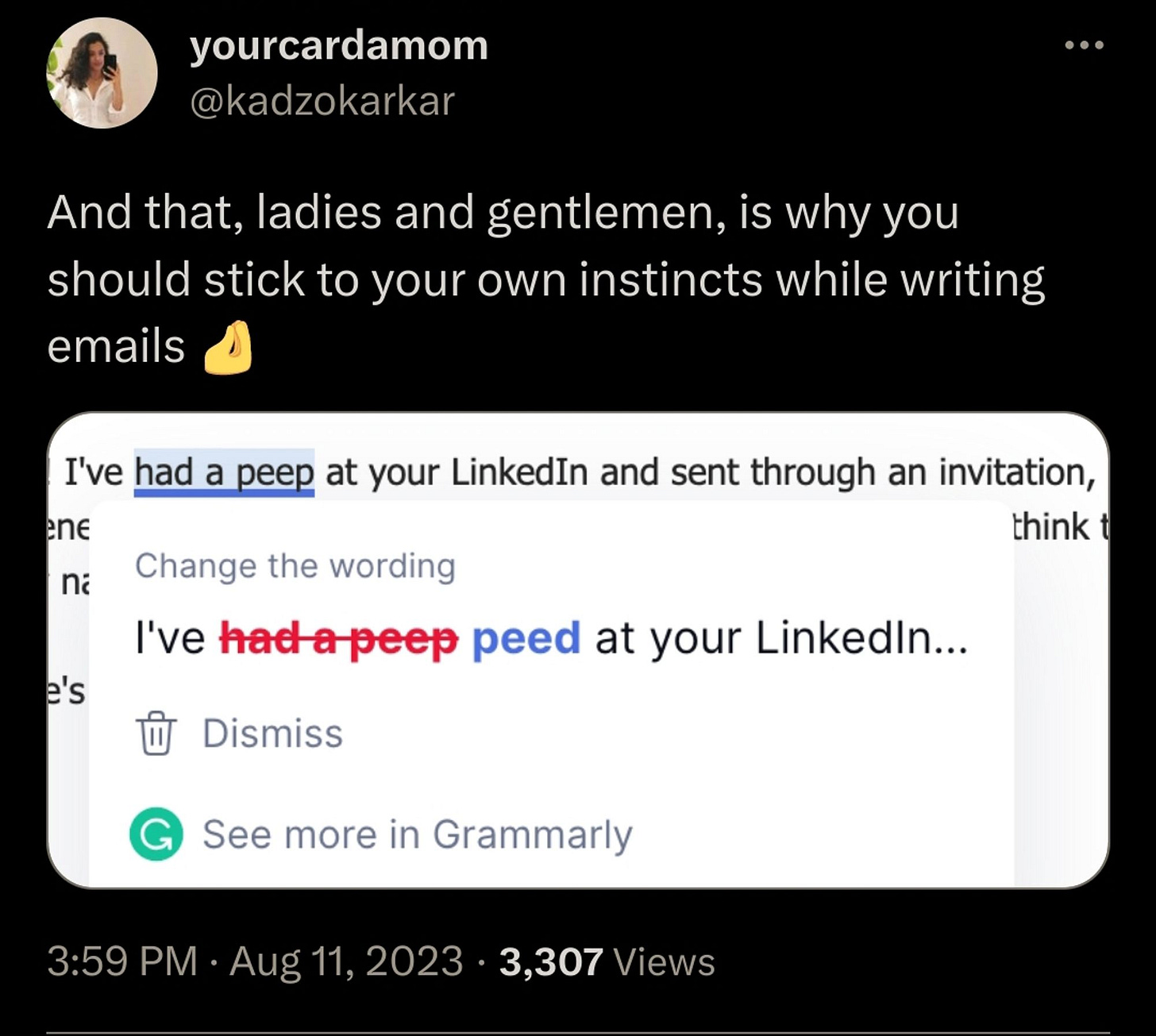

I hardly think that case (1) is objectionable, considering that Microsoft Word has been underlining our language mistakes in red for twenty years now. This is meant to simulate the back-and-forth of writing a paper and getting red marks on it from your instructor, and AI only accelerates that process further. One could say, if students want to use ChatGPT (or the AI-powered GrammarlyGO) to punch up their already-written college essays, all power to them.

Still, there is something to learn from this example. If you type out an essay full of language mistakes in Word and you want it fixed up, you have one of two options: you could either thoughtlessly right-click on all those red squiggles and accept all of Word’s corrections, or you could go through each suggestion one by one and accept or reject the suggestions as needed (“should I really remove the comma here?”) The process of going through Word’s suggestions and evaluating them teaches you how to write better, especially if you’re a non-native English speaker, which is the value of doing it yourself.

ChatGPT doesn’t offer the same learning experience, at least not unless you specifically ask it to spit out an itemized list of all its corrections, which is not the greatest user experience. It’s just “okay essay in, good essay out” with zero opportunities for learning. This is a totally valid critique of ChatGPT, because it actually addresses the value proposition of education: the process of writing and correcting an essay teaches you how to write a better one, and students over-relying on AI tools means they’re missing out an gaining valuable skills.

The pro-tech counterpoint to this might be something like this: “Who cares? Nobody ‘needs’ to know how to wind up an alarm clock, read a paper map, code a computer with punch cards, or operate a VCR player anymore. So why do students ‘need’ the skill that auto-correct provides for them? Besides, holding international students who are non-native English speakers to the same standards as American-born students isn’t very equitable; ChatGPT helps level the playing field.” I’m not sure if I agree with this 100%—after all, what if the Internet goes out one day, and all your co-workers find out you can’t spell? This is to say nothing of how these tools can get things wrong: even Word regularly ignores my mistyping of “tool” as “toll” or “files” as “flies”. That said, I get the spirit of what’s being said here, especially when it comes to helping international students learn English. I think it’s the job of teachers everywhere to better explain the value proposition of learning how to edit on your own. Or, consider this valuable activity: have students go through the exercise of comparing and contrasting their self-written work to their AI-corrected work, highlighting all differences and writing a short reflection on what they learned about proper writing practices. There’s a lot that we can do with AI that isn’t outright rejecting it, if we can just be a little creative!

Case (2) gets a little bit more ethically hazy. One can very easily use ChatGPT to turn a list of bullet points into a paragraph or a short essay. This is where my inner Tech Bro chimes in again: “That’s great! Students can save so much time with the busywork of writing sentences and correcting grammar. That way they can focus on the core of what the assignment is about: developing great ideas and strong arguments.” I’m a little bit less comfortable with this, but once again, the Bros are pointing in the direction of something true about modern education.

I wrote about this in my piece about the industrialization of education, but in short, there’s a huge disconnect between what teachers say education is for (their supposed teaching philosophy) and what actually goes down in the classroom (their actual teaching style). For example, we instructors say that we want students to develop their own unique perspective and writing voice, but then we punish them (with poor grades) for deviating slightly from our ideas of professionalism or sharing opinions that differ from our own (I’ve had numerous trans students share with me that they’re afraid to use a pro-trans analytical lens in their work, due to fears that their instructors might be transphobic and not take it seriously).

The grading scheme of most college classes reflects this reality as well: more often than not, students submit their work once with no opportunities for feedback, only to receive a grade out of 100, with marks off for things like improper or poor sentence structure. Also, this assignment is probably just one of several across many concurrent classes that you have due within a few days of each other, which you have to complete on top the responsibilities of the extracurriculars you’re a part of (because how are you supposed to get into a good job and/or med school without being president of at least 3 clubs?) and your part-time job (because how else can one afford college right now?) In this scenario, students are simply making the rational choice to use AI tools to make it “perfect” (as in, aligned with instructor expectations for good writing) the first time.

My perspective is very much pro-student; if a student is taking a shortcut through their assigned work—relying on chat bots to write their essays, or even cheating on exams—it’s because they don’t see that work as valuable. Or, at least not as valuable as the other 20+ other things going on in the lives of modern students: the other 5 classes they’re taking, applying to jobs, paying rent, caring for their families, maintaining their physical and mental health, etc. This is my rationale for ungrading in my classroom, where I have abolished exams and try to give as many opportunities for feedback as possible before administering a final grade, which I only do because of ABET requirements. It’s also why I explain to students the value of what they’re doing, rather than having them complete work “because I told you so”. Every one of my assignments is linked to specific learning outcomes and no assignment is extraneous. I believe that if more instructors were transparent about “why” students were doing what they were supposed to be doing—what skills they’re meant to be developing—fewer students would be inclined to use AI tools as shortcuts.

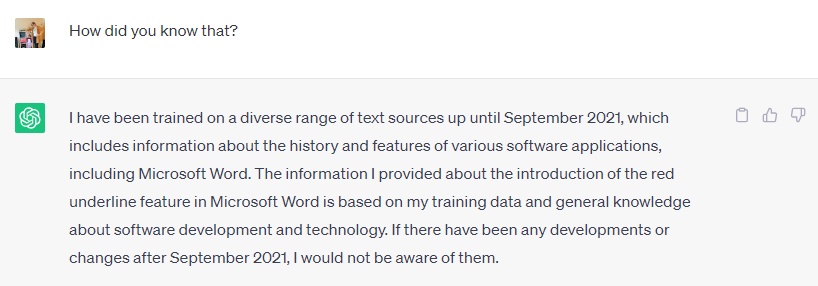

Then there’s case (3), which I will admit, does send me into a bit of a frenzy. I’ve heard of many students using ChatGPT as a search engine, akin to Google. I can see why they do so; the information given to them by ChatGPT is usually seen as more relevant to the actual question. When writing this very essay, I wasn’t actually sure when Microsoft Word first introduced the red underline feature, so I first turned to Google. When it only returned results for Microsoft’s own Community Answers pages about how to turn off the feature, I asked ChatGPT the same question, and it provided one in mere seconds.

The conversational format of chatbots also allows for more detailed answers to questions; one could ask “explain this more simply” or “explain this like you were a STEM professor” and the tool will deliver. In our survey to UMass students, plenty of students reported to us that they preferred ChatGPT’s replies to Google searches for these reasons and more.

One small problem though: CHATGPT IS NOT A SEARCH ENGINE.

Across all the content I’ve created in the past two years, the through line is a deep concern with how technology (when controlled by corporations) limits people’s ability to access information. In an era where much of what we consume is dictated by an algorithmic feed, it is critical that every single person have the media literacy skills to look at multiple sources of information and synthesize the truth. That’s why it is essential that instructors explain to students the inherent limitations of ChatGPT.

Let’s set aside ChatGPT for a moment and talk about Google. Google’s monopoly on advertising, and information more broadly, has been a problem for decades now. More than a quarter of users don’t search beyond the first Google result, and the vast majority of users don’t scroll beyond the first page of result. Practically speaking, this means that “truth” is a matter of what Google’s own technology chooses to index and present to its users in the first few pages of a search.

This leads to some problems. For example, if you Google the word “autogynephilia”, the thoroughly-debunked and violent idea that trans women only transition as part of a fetish, you’ll get some interesting results. The top link will be a “card” presenting a straightforward, uncritical explanation of Ray Blanchard’s transsexual typology. The next will be a piece from disgraced ex-sexologist Anne Lawrence affirming the condition’s reality. Only three of the first ten links refute the idea of autogynephilia, two of them being the same article by feminist scholar Julia Serano (both are locked behind a journal paywall, of course). As you can see, Google’s monopoly on information—what it chooses to index, what information it allows to float to the top—was already a problem.

But at least with Google, you could read through these top ten links and hopefully discern the truth (in this case, that trans people are more than just perverts). At least with Google, you can reliably search for any news story, read through multiple sources—one from ProPublica, one from Vox, one from Fox News—and probably synthesize something resembling actual Truth. ChatGPT, not so much.

First things first, ChatGPT does not have access to the entire web, it only has access to a sizeable-yet-relatively-small pool of data dating back to September 2021. ChatGPT is also a large language model, not a source from which to gain truth; scientifically speaking, it’s a stochastic parrot, meaning it forms sentences by starting with a word and guessing the probability of the next word in the sentence, over and over again until your college essay is formed. This makes having ChatGPT write college essays a bad idea, especially when you consider that the tool literally makes up fake sources, providing users with random names, fake journal titles, and DOI links that point to nowhere. Infamously, a lawyer got in trouble for using these fake sources a few months ago. So naturally, when you ask for an answer on ChatGPT, your reply can’t be fact-checked, at least not on ChatGPT. Its answers don’t pop up with links to read further nor does it tell you “where” it got its information; you just have to trust what it says. Once again, the skill that people ought to be gaining from doing their own research—the ability to discern between news sources, assess their credibility, and form their own opinions—is being obliterated by AI. When tech does the thinking for us, humans lose every time.

This all gets even worse when you consider that ChatGPT can simply be wrong sometimes. In fact, it can be wrong more often than not: a study published this week compared ChatGPT responses to Stack Overflow queries about software engineering, finding that 52% of the AI tool’s answers contained inaccuracies. Concerningly, these ChatGPT responses were still preferred by users nearly 40% of the time due to their “comprehensiveness and articulate language style”.

Students need to be able to know the limitations of ChatGPT. Without a doubt, students are going to start using these tools more (if they aren’t already), especially as they improve to the point of being able to produce higher-quality writing, perform full mathematical derivations with work shown, and more. So we ought to prepare our students to be technologically literate and media literate. We ought to explain to our students the value of what they’re doing, what skills we’d like them to gain from their assignments, and encourage transparent and equitable learning practices. We can also try new types of assignments that challenge our students in ways that they couldn’t be before, allowing education to evolve into a more liberated version of itself.

However, it seems like many educators don’t want to teach students the nuances of AI learning tools, or think critically about how they can improve their teaching style; they want to punish students for deviating from their narrow expectations. Distilling that notion down even further: educators don’t want to teach students; they want to punish them.

This is part of what Jessica Hatrick calls “the carceral classroom”. Some may call it a reach, but I see great parallels between the prison system and certain classrooms. Rather than identifying a need that students have—to save time, to solve problems creatively, to gain career-relevant skills, to be loved—some teachers would rather punish their students, with “time out” or detention in grade school, with academic probation in college, and poor grades across all learning levels. Poor grades and other punitive measures, of course, come with the risk of students wasting thousands of dollars having to repeat semesters of college, or simply dropping out of college entirely, a phenomenon known as the “school to prison pipeline” which disproportionately affects students of color.

I have more to say about the carceral classroom which I will another time (subscribe for more analysis!), but suffice it to say, I don’t want teachers to have another excuse to kick students out of college and into the prison system. Blanket bans on AI in the classroom are sure to create more opportunities for professors to discriminate against students that they don’t like. In fact, it’s already starting: some professors are turning to software that scans essays to try to determine if they were written by AI. These programs, however, are known to discriminate against non-native English speakers, with many students already being accused by their instructors for cheating when they never did anything wrong. All of this is part of a long pattern of surveillance in education and teachers having a militaristic teaching style that obliterates student agency and creativity. Carceral logic and teaching should never mix.

I am all for critiquing technology. In fact, I love doing it! But having an adversarial relationship with your students is not the answer. Students want to learn. Students want to get a high-quality education. Students want to gain valuable skills. Students want to prepare themselves for their careers. When they do “cheat” or “take shortcuts”, I believe it’s completely out of necessity. It’s our responsibility as teachers to (a) make cheating unnecessary by changing our assignments and reducing student stress, (b) explain the value of our assignments to students, and (c) educate our students about the limitations of AI learning tools.

All of this nuance is missing when we create blanket bans on AI tools in the classroom, and more importantly, historically-excluded and marginalized students are getting hurt far worse by these militantly anti-AI practices. Much like how abstinence-only sex education results in more unwanted pregnancies and STDs, thus the best thing to do is to teach young people about safe sex practices as well as the dangers of sexual activity, we can embrace ChatGPT while also talking about its limitations and dangers.

Currently Reading

Related to the above piece, an article about the shortcomings of ChatGPT in chemistry education.

The great Lily Alexandre’s review of a “cyberpunk restaurant” in Montreal.

Illinois just became the first state in my country to pass a law protecting child influencers. As the proud auntie of a baby whose image, name, and birthday has been forbidden from social media, I am thrilled about this! More protections for children, please!

Unfortunately, most states’ attempts to make a safer Internet has involved banning LGBTQ people and sex workers from it. Please contact your legislators about stopping KOSA (Senate Bill 1409) today!!

Watch History

The two best takes I’ve seen on Barbie (2023) have come from Broey Deschanel and verilybitchie, both of whom grapple with the films’ inherent capitalist incentives without being dismissive of the film as a whole.

The best case I’ve seen for nationalizing the streaming services.

Sophie From Mars’ “The World Is Not Ending”, a must-watch for those afflicted with climate anxiety.

A video essay on the politics of self-diagnosis.

Bops, Vibes, & Jams

A new Jungle album, with bangers like “Back on 74” and “I’ve Been In Love feat. Channel Tres”! As usual, the music videos are half the fun.

NEW MITSKI ALERT!!! THIS IS NOT A DRILL!!

The funnest EP I’ve heard all year so far is “LFG” by electronic artist INJI. Listen to “THE ONE” and “MADELINE” to see what I mean.

And now, your weekly Koko.

That’s all for now! See you next week with more sweet, sweet content.

In solidarity,

-Anna

Interesting insights about how students use AI. Also, I like your teaching philosophy. I hope my kid has teachers and professors who think similarly.