ChemE Design Justice: A First Attempt

On chemical engineering, workshops, and teaching reflections.

Happy Almost-The-End-Of-The-Semester! I am crawling toward the finish line, and despite the fact that every day of these past four months has been a battle to get a good deck of slides ready for the next lecture (of which I had three per week), I can confidently say that my first semester as a teaching faculty went pretty well!

This was my very first time teaching Process Dynamics and Control, a course for chemical engineering (ChemE) seniors all about how to design control systems for chemical processes. That is to say, how to keep a chemical plant from going off the rails and exploding. For my first time, I decided to mostly stick to what the previous instructor had done; control theory content interspersed with occasional in-class problem solving.

I had a few of my own original contributions (abolishing exams in favor of smaller, lower-stakes assessments; *occasionally* integrating DEI/social justice themes into my lectures; using an “ungraded” approach to the final project; handing out a syllabus that was literally a zine). But as much as I wanted to ~completely~ flip the course on its head (go totally gradeless; implement social justice elements into *every single* lecture; have students make memes as a learning activity), I thought it best to do one “traditional” run of the course first. That way, I could best familiarize myself with the core content of the course and observe trends such as “what concepts do students tend to get stuck on”.

Sometimes, you have to learn the rules so you can know how to break them.

One of the “unspoken” rules of engineering for the longest time was that “politics has no place in the classroom”. I happen to disagree, not only on the basis that neutrality is itself a political position, but that engineers have huge sway in how societies get constructed. The push towards DEI (diversity, equity, & inclusion) in STEM has focused largely on extrinsic values; more diverse teams result in higher citation counts, etc. That much is true, but we need to be careful with our framing: are we nurturing diversity so as to do the same Western science with a greater impact, or should we do it so we can change how we do our science entirely?

This gets to an even deeper question about the very identity of our field: What do chemical engineers even do? Who are we? In my mind, ChemE is defined by two traits. On one hand, ChemE as a discipline has always been associated with industriousness [derogatory], its origins traceable to the large-scale processing of crude oil, soda ash, dyes, and other things that we (capitalists) have decided “we need a lot of”. Chemistry, but make it bigger. On the other hand, us ChemEs are an inherently collaborative people. By virtue of our jobs, we need to reconcile chemistry, physics math, materials science, biology, and numerous other fields. A class of ChemE graduates can branch off into polymer science, biomedical engineering, software development, or any number of fields. We are interdisciplinary AF, and we are systems thinkers. So I believe in my heart that we are more than capable of tackling social justice themes in a deeper way than doing so for higher citation counts.

Which is why I spend the last week of my Process Control course talking about design justice, indigenous science, and how chemical engineers can work with their communities to build resilience against climate change.

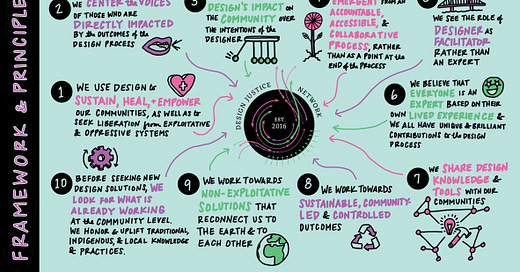

Design Justice is a body of ideas that re-imagines how products, processes, and more are designed. The core tenants involve (among other things) assessing who is involved in design processes, who is benefitted by the design process, and who is harmed by a design process. From there, we can change our design processes to involve those who might be most harmed. It’s a simple idea, and yet it’s still semi-rare to find chemical engineers who are thinking in these terms. I even had a hard time finding classroom-ready workshops for students that had ChemE-specific examples.

So I made my own! You can find all my slides from this past week of class in this Dropbox folder.

On Tuesday’s class, I largely focused on broader issues in the field of ChemE process control, including emerging trends in the field. Big data, cyber security; stuff that’s cool but that I couldn’t get into this semester because we had a lot of Laplace transforms to do (it was my first time teaching this course, remember?) I ended that class by questioning the industrial element of ChemE entirely, comparing industrial farming practices to the indigenous Three Sister’s planting method. The former involves monocropping, heavy pesticide use, and air pollution, among other atrocities. The latter involves planting three different species together so that each can benefit one another. I first learned about this practice from Braiding Sweetgrass and this concept of self-sustaining symbiosis has been rattling around in my brain ever since.

“If you think about it, this is some pretty incredible chemical engineering!” I exclaimed to my students, some of whom perked up at this deviation from the usual discussion. “By all metrics, this form of planting is superior, but when white colonizers came to this land, they thought it was silly to plant things so close together. Racism got in the way of good engineering, and they went on to implement a worse system.”

“On Thursday, we’re going to be digging deeper into this area of thought and asking how chemical engineers can worth with different communities to develop better solutions to chemical engineering problems.”

Two days later, it was workshop time. My seniors were primed and ready to start thinking critically about what chemical engineering is and what chemical engineers do. [Reading this next part is easier if you follow along with my slide deck!]

I started class by prompting students to think about what community means to them; “what communities do you consider yourself a part of?”. I then shared a non-STEM example of working class history: “Who here has eaten at Halal Guys?” In the late 80s/early 90s, there were a lot of Muslim taxi cab drivers in New York City who needed a quick way to grab food while on the job. So, the Muslim community came together and developed a solution: street vendors, such as the now-famous Halal Guys.

“I bring this up to show that when I talk about ‘technology’, I’m not just talking about things like the iPhone where a bunch of smart guys suddenly bestow upon the population the gift of some amazing device; technology can be developed by communities, for communities. And chemical engineers can think in this way too!”

I then went on to quickly summarize an anti-example—ChemE injustice—a series of decisions by ChemE goons and the EPA that sparked the birth of the environmental justice movement in Warren County, North Carolina. After the illegal dumping of PCB onto highways, the state wanted to dump 60,000 tons of PCB-contaminated soil near a largely Black community, which still impacts that community to this very day. As a class, we broke down the groups in this situation; who was involved, who benefitted, and who was harmed.

After doing this first example as a class, I then quickly presented 3 additional case studies of chemical engineering gone wrong, and asked students to work in groups and choose one case study to evaluate by the same metrics. To help, I gave them all a physical worksheet with the above Venn diagram on the front and guided questions on the back [this is also in the Dropbox!] I also gave them QR codes with links to learn more about each of these case studies.

The Keystone XL pipeline, proposed by chemical engineers and the businessmen they work for, which was thankfully shot down by Biden early last year

The ExxonMobil Baton Rouge green belt, a greenwashing project where the oil giant bought land to preserve it and prove they weren’t totally evil!

Nestlé/Bluetriton’s heinous practice of pumping water out of the earth, usually at no charge, and selling it back to us for profit

As stated above, undergraduate education in my field is typically focused on the industrial-scale production of commodity chemicals, from soap to gasoline to everything in-between. Nowhere is that more present than in Process Control, a course entirely predicated on the existence of large unit operations (bioreactors, heat exchangers, etc.) which need to be “kept in line” with the use of sensors, PID controllers, setpoint tracking, and more. In the same way that capitalism abstracts and alienates all of us from each other, our labor, and the systems responsible for getting food onto our dinner tables, an industrialist ChemE education abstracts the design process from the people who are impacted by the engineers’ decisions.

This makes having a deep discussion on DJ/EJ as it relates to ChemE somewhat of a challenge. As opposed to critiquing, for example, biomedical devices made for consumers (where there is a clear way to involve the people you’re designing a product for), us ChemEs are left critiquing huge corporations that are So Clearly The Villains that it almost feels trite to do so. “ExxonMobil? The bad guys?? No way!” Part of me fears that exactly zero of my students (who I will remind you were born in the year 2000 and have always lived under the spectre of climate change) had a mind-blowing revelation via this exercise.

Still, I think it’s better to challenge the still-dominant ideas about what chemical engineers do than to leave it unstated, and to provide students with a framework for critiquing engineering design practices going forward. I drew a large version of this Venn diagram on the chalkboard and after going through all 3 case studies, we collectively concluded that (a) those who are harmed are almost never involved in ChemE decision-making while (b) those who benefit are almost always involved. Progress!

I didn’t want the whole class to be a bummer, though. Why should it be? In my mind, design justice is about abundance, radical optimism, creating positive change. So, for one more group activity, I provided students with three new case studies…

Miyuki Hino earned her B.S. in chemical engineering and then went on to develop storm drain sensors for coastal towns who experience chronic flooding (the use of sensors makes this directly related to process control!!)

The CoolAnt Beehive (which I talked about in a previous newsletter), essentially a giant heat exchanger (a core ChemE unit operation) except made of clay, currently being used to cool an electronics factory in India

Fireproof building materials derived from mud, loosely based on Indigenous adobe home design and meant to protect people in California from wildfires

You may notice that all three of these case studies have a theme: chemical engineering for community resilience against climate change. Currently in ChemE, most of the conversations about climate resilience involve protecting supply chains. This is important, but I’d like to shift the conversation towards how chemical engineers can take their skills/knowledge to better help people in their own communities. Transfeminism reminds us to “be in your own body, be in your own place”, and I tried to embody that here.

After another period of group work, we rejoined as a class to discuss these cases of chemical engineering “done right”. Together, we collectively found that chemical engineers can indeed do their work in a way that involves end users in the design process. Hooray!

The students really engaged with the activity and I was incredibly proud of them! I had also intended end class by having them think about how DJ principles could apply to their final project (which has a required Broader Impacts portion), but we were out of time. Live and learn!

In the coming years, I hope to devote even more in-class time to discussing these examples of ChemE design justice. Instead of doing it at the end of the semester (especially the week following Thanksgiving Break when many students have already mentally checked out), this interactive workshop activity could be implemented throughout the semester and be a recurring theme in homework assignments, project deliverables, and more. A common criticism I have in “DEI”-related activities is that they’re not implemented seamlessly into STEM courses, but rather “tacked on” in such a way that students can tune out.

I also want to involve more people who have been directly harmed by the decisions of chemical engineers in the development of this activity. If I’m discussing indigenous science, it only makes sense to involve an indigenous scientist, after all. I made my slides about companion planting in collaboration with the Native American student association back at UConn when I was a grad student there, which grants some legitimacy, but we can always do better. ChemE students, more than perhaps any other, need to consider how extractionist ways of viewing the world are wrong, but perhaps not only from a white lady such as myself. In past years, I held cogenerative dialogues with students from my classes and had them lead a module on environmental justice; perhaps these ideas can be synthesized?

Many white DEI practitioners face the dread of “Oh god am I doing enough?? Am I doing more harm than good??” Which is important to consider; discussions of racism/colonialism/etc. in a classroom need to be handled with care, especially when students who’ve been victims of these horrors are present for those discussions. But we have to try! (And, you know, collaborating with and fairly compensating people of color helps too.)

This first attempt at a ChemE design justice workshop wasn’t nearly perfect, but like everything else in my first semester of teaching, I had to start somewhere! Let me know what you think of this workshop concept in the comments below or on social media (Bird App) (Eleplant App)!

Currently Reading

I just posted a new podcast episode all about labor strikes as a tool for fighting climate change! Don’t forget to check it out! <3

A recurring theme in this section is “well I could’ve told you that, but hey, I guess there’s data now”. Here’s the latest entry: a new article demonstrating racial disparities in NSF funding rates.

Speaking of indigenous rights, this past week I got to watch the film Powerlands and also attend a live panel discussion with its director, Ivey Camille Manybeads Tso. During the conversation, Ivey mentioned a new initiative at Northern Arizona University that will let Native American students attend tuition-free. Sounds like I have a new action item for UMass…

Rest In Power, Bubbie ✊🏻

Watch History

With all the recent fuss about Established Titles, we have yet another opportunity to reflect on how colonialism has warped our brains. Even though the whole operation was a sham, the fact that a LOT of people paid real money to cosplay as colonizers (own land in a country they may never even set foot in) says a lot about the soul of our country.

I may write more about this in the Super Cool Paid Version of this newsletter, but many different people are picking apart the new Pokémon game and why it’s so buggy. I personally blame capitalism, specifically the crunch conditions that must be present at Game Freak in order to pump out games, merchandise, an anime, and a trading card game every 3-4 years.

From More Perfect Union, the legend behind the infamous “insulin is now free” tweet (from the even-more-infamous 2-day period when Twitter verification cost $8).

Bops, Vibes, & Jams

My 2022 Wrapped top genres were, in this order: Indie Pop, Pop, Alternative R&B, Mellow Gold, and Hip Hop. Check out my top songs of the year right here!

And now, your weekly Koko.

That’s all for now! See you next week with more sweet, sweet content.

In solidarity,

-Anna