Real quick up top: I’m now giving 50% of my Substack income to help a family survive in Gaza. In December 2024, we sent $80! Thank you so much to my paid subscribers! If you want to help too, consider upgrading to the paid tier; if you do, you’ll get four hot takes per month instead of two!

This week, we need to talk about the study that made us all panic about our black kitchen plastic. But first…

Dr. Anna Marie’s Three Questions To Ask When You Hear The Phrase “A Study Said So” In A News Headline Or Viral Video…

What type of study?

What type of journal?

What are its limitations? (E.g. sample size, methodology, statistical significance, conflicts of interest, etc.)

It’s unfortunately pretty rare that a news story about plastic hits the mainstream. It’s even more unfortunate that when one does, it usually leads to mass panic. We’ve seen this before with plastic straws, period products, and every time a new finding comes out about microplastics. (Side note: here’s another write-up I did about plastic waste!)

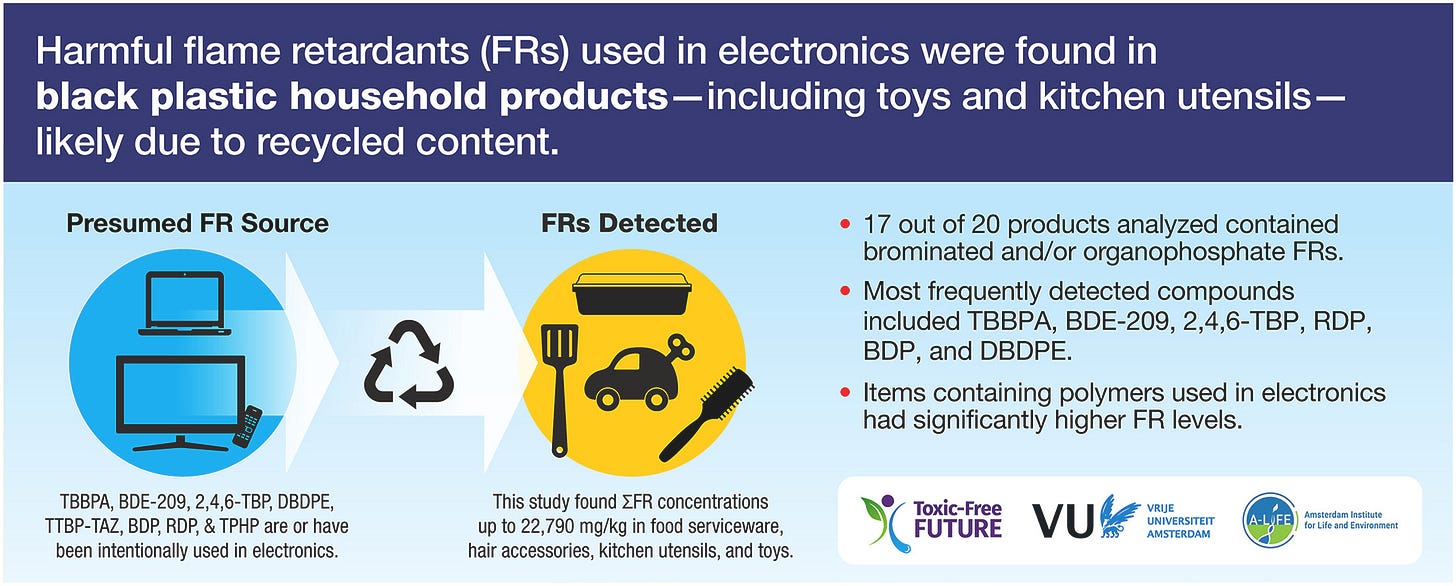

You probably did hear about this one: a study in the journal Chemosphere found that black plastic items such as kitchen utensils (spatulas, serving spoons, other food service ware), and kid’s toys contain high amounts of brominated flame retardants (BFRs) and organophosphate flame retardants (OPFRs), which are widely known as hormone-disrupting and carcinogenic (cancer-causing). Here are some links to some news write-ups from traditional news outlets (1 2 3) and one sustainability-focused publication (4). Essentially, many of these plastics contain recycled material from e-waste—think the plastic enclosures for televisions, remotes, phones, etc.—which contain flame retardants to make those electronics safer. While recycling plastic is an important part of a sustainable, circular economy, it can be incredibly dangerous for plastics that contain non-food safe chemicals to later end up in materials that directly touch food. Our recycling infrastructure needs a massive overhaul to address this problem by carefully tracking what types of products end up being recycled into what, and the everyday consumer should be wary of black kitchen plastics since they are likely to leach these dangerous chemicals into our food.

This story spread widely for a few reasons, but perhaps most importantly, it came with a pretty simple directive: “get rid of this specific type of plastic and replace it with wood or metal”. This easy-to-execute order stands in stark contrast to microplastics, whose stories usually end with “they’re already in everything, including us, so I guess there’s nothing we can do, except end capitalism maybe?” This leaves no room for any material action, other than from snake oil salesmen who will try to sell you a pill that magically detoxifies you from microplastics (spoiler alert: no such technology exists).

Anyway, once the journal article was picked up by news sources, then by content creators from across the political spectrum, people started throwing away their black plastic kitchen utensils in droves. As someone who generally advocates for finding alternatives to plastic whenever possible, I personally believe this is a good thing: the general public has no concept of the hazards that plastics contain. As an expert who teaches a class on this very subject, one thing I’m always sure to highlight to my students is that “plastic” is not just one thing: not only are there many types of plastic (PET, HDPE, LDPE, PVC, etc.) but even within each of these categories, every product made with that material is wildly different. Despite sharing a base polymer, a PVC pipe and a PVC music record have totally different compositions: the pipe will contain heat stabilizers, plasticizers, flame retardants, antioxidants, and fillers to make it rigid, while the record will contain anti-static agents, pigments, lubricants, and also stabilizers and plasticizers, but in completely different amounts to the pipe since the pipe is made with extrusion and the record was made with compression molding. Similarly, two plastic bottles from different manufacturers will have totally different amounts of UV stabilizers, slip agents, oxygen scavengers, and more. In other words, even if you know what the base polymer is for any given plastic product, you have literally no idea what other kinds of cancer-causing chemicals might be in there. The fact that even the non-specific way we talk about plastics (e.g. “black plastic”) is not nearly as descriptive enough to even start to have a conversation about the scale of the harms associated with these materials!

However, none of this is why I’m writing this piece. The most interesting part of this story, to me, is what happened next.

The Chemosphere study looked at many flame retardant compounds found in black plastic, including TBBPA, BDE-209, RDP, BDP, and DBDPE. In one calculation, the daily intake of BDE-209 (decabromodiphenyl ether) was estimated to be 34,700 ng/day. In the original article, the authors used the reference dose—the U.S. EPA's maximum acceptable oral dose of a toxic substance—of 7,000 ng/kg body weight/day. However, in a multiplication error, they stated that the maximum allowable dose of BDE-209 for a 60 kg (132 lb) adult would be 42,000 ng/day, instead of the correct value of 420,000 ng/day (7000*60=420,000). Since the article warned that the estimated daily intake of BDE-209 was 34,700 ng/day was close to the incorrect maximum acceptable intake of 42,000, but far from 420,000, on December 15th, the authors issued a correction clarifying the error but stating that it “does not affect the overall conclusion of the paper”.

ARE YOU ENRAGED YET?? Apparently, you should be, because this one (admittedly silly) math error about one of the many chemicals addressed in the paper was also taken up by both mainstream news and content creators. Despite the fact that BDE-209 was only one of the several chemicals studied, and the fact that 34,700 ng/day is still an unsafe dose for, as an example, a 5 kg (11 lb) baby, this error was used by some to imply that the study was “blown out of proportion” (as well-respected science communicator Hank Green stated) or should be rejected entirely.

“How a simple math error sparked a panic about black plastic kitchen utensils” headlines the article shared by Green. “Recent panic over black plastic started with a math error” reads another in Popular Science. “Multiplication and mass fear” warns Mashable. Each of these articles makes sure to point out that the study was carried out by Toxic-Free Future, an environmental advocacy group, perhaps to imply a level of bias towards a certain conclusion. They also use the word “panic”, which we culturally view as “bad events where the public is misled into doing something stupid”.

We should be surgical about this. Yes, it was bad that the study made a math error. Yes, perhaps the study was biased because of who it came from. But this doesn’t necessarily mean we should throw the baby out with the bathwater: the plastic you use in your kitchen is still dangerous, especially for the many other chemicals that the study looked at, and you should probably seek alternatives. Interestingly, despite most of these newer articles clarifying somewhere that “BDE-209 is still bad for you” and “you might want to still be wary of black plastic”, this hasn’t stopped people, especially content creators, from casting doubt on the study as a whole, and even scientific journals in general.

Let’s return to our questions from before…

1. What type of study?

As I’ve written about before, the Chemosphere article is a cross-sectional study: it looks at a specific population (one collection of black plastic) at a single point in time (the time of the study). This does not mean the study is worthless, as it could point toward a trend that might be reproducible in other studies. If it turns out these results are not reproducible, then oh well, that’s just something that happens in science sometimes. A single scientific paper coming to a conclusion is not as significant as many papers coming to the same conclusion.

2. What type of journal?

The next question we should get used to asking when we hear “a study said so” is “what is the quality of the journal publishing this result?” Chemosphere is, admittedly, not the most credible journal in the world. Just a day after the correction was made to the black plastic article (though likely not because of that correction specifically), the journal had its impact factor revoked due to longstanding concerns about its quality. From Retraction Watch…

Chemosphere has retracted eight articles this month and published 60 expressions of concern since April. As we’ve noted elsewhere, removing a journal from Web of Science means Clarivate will no longer index its papers, count their citations, or give the title an impact factor, which can have negative effects for authors, as universities rely on such metrics to judge researchers’ work for tenure and promotion decisions.

Yikes! We should make no excuses for this: this is a lower-quality journal. That doesn’t necessarily mean the black plastic study is “not true” or should be thrown out—we don’t know if, for example, the study authors tried to get their work into a more credible journal and failed so they ended up here—though it does call into question the quality control standards in place at this journal (potentially explaining how the math error from before slipped through).

3. What are its limitations?

What other studies could be done to refine the conclusions reached by the paper in question? How about a longitudinal study on black plastic utensils made over time, for example looking at utensils from the 70s, 80s, 90s, and so on, to show whether the level of BFRs has been increasing over time? How about looking at black plastic from different parts of the world, or from different manufacturers, to determine which facilities are pulling from e-waste more than others? Finally, once many studies on black plastic have bene published, a meta-analysis that looks at all of the studies and comes to a final conclusion on the issue would be the gold standard for directing policy on black plastic recycling. A single scientific paper from a low-impact journal may not be enough basis for directing policy, or even making a change in your daily life. However, it could be a jumping-off point for future studies, and we also shouldn’t necessarily have to wait until 200+ studies are published on a subject before we craft public policy.

Problems always arise when we try to convert a non-binary input into a binary output. In this case, the inputs we’re expected to synthesize a conclusion from include:

raw data on how several carcinogenic and hormone-disrupting chemicals exist in plastic kitchen utensils and other household products

guidelines from the EPA on what levels of these chemicals adult humans should be exposed to

the conclusions reached by a potentially biased team of scientific researchers

the quality control standards of a potentially questionable scientific journal

one’s media literacy skills, including an understanding of the ways in which both mainstream media and independent creators are incentivized to sensationalize news stories to reach binary conclusions

the question of whether we should trust the United States government’s standards for what the acceptable level of toxic chemicals should be

the question of what truth is, and how we truly “know” anything

…while the excepted output is: Should I replace my plastic kitchen utensils? (Yes or no)

My hope is that if we can start asking better questions about the science we read about, we can reach better conclusions.

Currently Reading

My first big read of 2025 is Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza by Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa. Fun fact: I first read this book in my freshman year of college for a class titled “Hispanic Literature in Translation”. My report on the book was apparently so good that it led my instructor to shake her fists and yell “How are you an engineering student???” I guess I’m just built different! Check out the book here.

A piece on Emilia Pérez, which went viral on TikTok this week after both transgender and Mexican users discovered the song “La Vaginoplastia”, a flatly-delivered number about an MtF sex change operation. My take, having not seen the film, is that the song belongs in a 1970s comedy movie (a la Myra Breckinridge), not a 2024 musical. If the sex change song was camp, a satirical sendup of conservative expectations about gender-affirming surgery, then maybe it would be fun, but it’s played entirely, uncannily straight. There are much better transition narratives out there.

Watch History

The new Verity Ritchie essay on the gender binary in video games.

In addition to my list, an alternative list of the best video essays of 2024.

Bops, Vibes, & Jams

The new SPELLLING song signals a great year in music!

And now, your weekly Koko.

That’s all for now! See you next week with more sweet, sweet content.

In solidarity,

-Anna

Been following you for a while on TikTok, really love your content and wanted to make sure I was able to keep following and supporting you! I saw you recommend Ground News, do you have any discussions on how to read that? I try to keep a critical eye on anything I consume, but I’m honestly not sure how to interpret Ground News. It looks like the summaries are AI generated?