Cheating is the Rational Choice

On ChatGPT, industrialized education, and falling in love with process.

It’s Tuesday, May 20th. At 5:27pm, I finish submitting final grades for both of my classes (Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics II and Polymer Processing & Sustainability). By 6:09pm, I’m embracing some beloved colleagues under the warm, dim lighting of a local speakeasy. Dessert cocktails in hand, we toast to our small victories, vent about the state of academia, and crack jokes about when we’ll actually be able to take a break.

It’s been an exhausting semester.

Grading still on the mind, one friend laments how many final papers she’s read that were “written by robots”. She teaches a class on writing for STEM students, and despite having a strict, repeatedly-enforced “no AI” policy, numerous college Juniors took the LLM shortcut. This, of course, led her to an immense frustration that culminated in a dramatic ending to her last class of the semester; she recalls saying along the lines of, “To those of you who didn’t use AI for your final papers, great job! To those of you who did, I’m sorry you felt like that was the only option you had”. The shaming was met only by silence.

She describes this as a “moment of weakness”, like a religious person might describe succumbing to temptation, but our group warmly validates her actions. She, unlike most of the strict anti-AI professors, is sympathetic to what students go through. Still, she can’t help but feel frustrated about her position, trying to explain the value of good writing to a group of students who came into the class believing that writing is a waste of time in 2025.

Generative AI is a shortcut to product that circumvents process. It’s a service specifically designed to circumvent friction to get you right to what you want: an answer to a question, a completed homework assignment, validation for your darkest desires, a simulated relationship. Removing friction has been the goal of Big Tech for its entire existence, with companies like Meta now aiming to replace real-life friends (frictionful, have their own beliefs and needs and schedules, don’t immediately text you back) with AI companions (frictionless, already agree with you, bend to your will, are there for you 24/7).

As Kyla Scanlon writes in her essay on friction…

I think what we're witnessing isn't just an extension of the attention economy but something new - the simulation economy. It's not just about keeping you glued to the screen anymore. It's about convincing you that any sort of real-world effort is unnecessary, that friction itself is obsolete. The simulation doesn't just occupy your attention, right, instead it replaces the very notion that engagement should require effort.

Education is fundamentally about friction. You try something, fail, and through failing you learn something. Most educators agree that this is how school ought to work, to some degree, but that’s not how our institutions are set up. Scientists say that failure is part of the scientific process and so we should embrace it, but our culture doesn’t reflect that reality: it’s nearly impossible to publish negative results in scientific journals, we hire people based on how much grant money they can pull in or by what school they studied in, and graduate students who “prove 700 ways to not invent something” never graduate.

All of education is in tension between two competing philosophies:

The Philosophical Argument: School as liberal arts education. Learning is intrinsically valuable; a society familiar with the arts, sciences, and history, and science is a more just, equitable, democratic, and ethical society. In school, you don’t just learn a series of basic facts, you learn how to learn so you can be prepared to solve complex societal problems. The college experience is an opportunity to be surrounded by a community of diverse learners with whom you can collaborate to complete projects and expand your worldview.

The Industrial Argument: School exists to prepare you for the workforce. Learning is instrumentally valuable; everything you learn is information you need for the workforce, mere data to be entered into the correct interface. The college experience—homework, exams, essays, projects—is just the boring, expensive step to get what you really want, which is a good-paying job.

Ideally, college should be a balance between the two, as I have argued before. But it’s undeniable that the pendulum has swung immensely towards the Industrial Argument, particularly in the STEM world. The point of writing an essay isn’t to learn how to read critically, synthesize information, and craft a good argument. The point of writing an essay is to hand in an essay so you can get good grades so you can get a job. In the industrial/instrumental mindset, you should be min-maxing your education by taking the minimum number of courses required by your degree program and taking shortcuts wherever possible; most of this won’t matter, you’ll learn what you need to learn for your job once you’re at your job. Every semester I advise undergraduate students to take advantage of the thousands of courses our university has to offer and take something that truly interests them, even it’s a 300-level course in a program they’re unfamiliar with, but every semester most students take what their peers have collectively deemed “easy As” (Sociology 100, the goof-off art history class, etc.). My friend’s biggest mistake was attempting to make an argument for friction in a culture whose motto is “Move Fast and Break Things”.

What I really need to stress is this: It’s not the students’ fault they act like this. It’s what we’ve trained them to do. In the STEM world especially, we’ve elected to act in service of industry rather than by what is philosophically right. In chemical engineering, for example, we primarily teach students how to optimally refine raw materials from the earth into commodity chemicals, without much discussion of why or for whom. We take for granted that fossil fuels, synthetic fertilizers, polymeric materials, and specialized catalysts must be made. The logistics or ethics of extracting these raw materials are never discussed (aside from my optional elective class on sustainability that I offer in the Fall), and there is certainly no discussion of the workers who have to actually work in the refining/manufacturing plants that these future degree-holders will design. The way we teach reaction kinetics is particularly abstracted from reality: we have students carry out the math on the simplified reaction “A + B → C”, often not even specifying what the chemicals A, B, and C are. The reaction could be green hydrogen production, fossil fuel production, polymerization, the creation of chemical weapons, or anything in between; the math doesn’t fundamentally change, just slot in the correct constants for each species (density, Gibbs free energy, etc.) at a later point when needed. It’s the most efficient way to teach the subject, but it leaves behind any conversation of ethics, sustainability, or relation to Land (e.g., does the methane reclaimed form biogas reactors or does it come from burning coal?) Here, I use capital-L Land as how Indigenous scholar Max Liboiron does, to specify land not as a resource to be extracted from but as another relation we’re responsible for. As usual, STEM presumes the universalism of knowledge, what Donna Haraway called “the god trick”. It’s perhaps not a coincidence that generative AI is the epitome of flattened, universalized knowledge; “we fed all this training data into the robot, so whatever summary it spits out must be an accurate synthesis of this information.”

As James Lang argues in his book about academic dishonesty, cheating in college is far more likely when four criteria are met: 1) an emphasis on performance (we can describe this as product-oriented as opposed to process-oriented), 2) high-stakes assessments on those performances (e.g., a grading scheme where 3 exams are each worth 30% of the grade), 3) an extrinsic motivation for success (education is instrumentally valuable rather than intrinsically), and 4) a low expectation of success (in STEM, this looks like the normalization of 40/100 being the class average on an exam). The problem isn’t that students are lazy or immoral; the learning environment that we (universities) created has naturally resulted in a generation of learners who genuinely don’t believe that writing will be useful in their careers and where “use in their careers” is the only thing that matters. This is to say nothing about the ramping expectations on young people to not only do well in your classes but to be active in various clubs, work in a research lab, and crucially, hold down a part-time job (unlike when my parents went to UConn in the 80s, you can no longer pay an entire year’s tuition with the measly income from a minimum wage summer job), all of which makes min-maxing your education (having the robot do your 8th assignment in 2 weeks) seem far more attractive. This kind of cheating—using generative AI to complete 100% of your assignment for you—is the rational choice in a system in which “job preparation” is the guiding principle of higher education and where students are forced to have a side hustle to afford their degrees.

“I really don’t want to be a fogey about this” my friend laments to me as we swish glasses of rosé. “I’m trying to think about technological innovations of the past, like how the invention of writing was thought to ruin our ability to memorize, or how the Internet changed how we look up information.” Educators generally don’t want to punish students; we know what students go through, especially younger faculty like us whose experiences (economically speaking) most closely mirror Gen Z’s. It tends to be older faculty who, having spent years finding information by perusing a physical library, become aghast at the idea that students are getting personalized learning support from a robot and conclude that the problem is shameful laziness.

At the same time, it’s hard not to be resentful; for all the talk about “ivory tower academics” with cushy tenure jobs, being a faculty member is not easy, particularly for non-tenure track teaching faculty like my friend and I. We Lecturers who, in addition to being paid less (much less), trade the stress of applying to grants and running a research lab for teaching 2 or more core undergraduate courses. We put an immense amount of effort into our teaching because we value education (intrinsically), so when students take shortcuts, those efforts are invalidated. On a base human level, it’s upsetting, even rage-inducing. In my Thermo II class this semester, I was able to clock the use of Gen AI when a student submitted their final project with references to papers that did not exist. LLMs, by virtue of being stochastic parrots, will hallucinate references to journal articles, so copy-pasting the paper titles into my search bar came up with zero results. This along with the formatting of certain sections of the report (bold title, bullet point, bullet point, repeat) were a crystal clear indicator that either ChatGPT or Copilot were used. This was eyeroll-inducing; if you’re gonna cheat, at least be smart about it! Just as we teachers need to understand where our overburdened students are coming from, students need to understand where our “moments of weakness” and lashing out are coming from.

The way to get students to stop using AI shortcuts is not to punish them for doing so, it’s to get them to fall back in love with process. Any creative person will tell you that the art they make isn’t a pure expression of what they pictured in their mind’s eye, you uncover the art through the process of making it. Any scientist will tell you that their greatest discoveries were accidents, results that they never went into research anticipating but emerged either as a result of completing many projects or from investigating a prior failure. We need to rethink our education system and consider how we can reject optimized, efficient, industrialized learning models and embrace friction, embrace failure. This is easier said than done, of course; when I read James Walsh’s recent report on how many students use AI, which practically went viral among college educators, I felt seen by the utter despair shared by fellow instructors. Yes, our education system needs to be overhauled in such a way that student knowledge is assessed authentically, but who among us has the time for that? Just like the students, we’re all barely scraping by.

Fortunately, some scholars have already begun the work. In their paper “Provocations from the Humanities for Generative AI Research”, Lauren Klein and colleagues rebuke generative AI while proposing next steps for academia. They boldly declare the value of the humanities—fields that are much more intrinsically motivated than STEM—put forward eight proclamations about AI that help to ground such a discussion…

Models make words, but people make meaning

AI requires an understanding of culture

AI can never be “representative”

Bigger models are not always better models

Not all training data is equivalent

Openness is not an easy fix

Limited access to compute enables corporate capture

AI universalism creates narrow human subjects

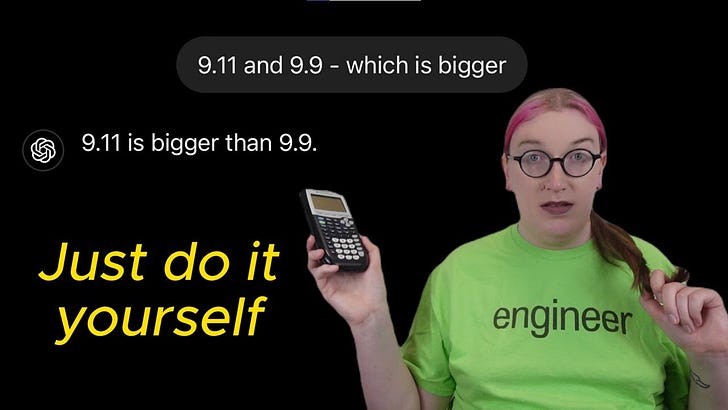

We should always be mindful of the tools’ limitations, which I discuss at length in my video on the subject (my “syllabus statement” on Gen AI was becoming so long that I ended up creating a 40-minute video explaining why my students should and should not use it).

No matter what, our conversations should always be student-centered. In Spring 2023, when ChatGPT was brand-new, the same colleagues I spend the night drinking with carried out a study where we directly asked students how—and why—they were using generative AI. That study resulted in a white paper that you can read now! Our approach was incredibly student-centered, which was a deliberate choice in an environment where the discourse around LLMs was driven entirely by teachers. In a way, it still is: ChatGPT is still the topic du jour among TikTok outrage merchants peddling the message that “we’re so cooked” because college students don’t want to write boring essays anymore. By and large, students at the time of our study were aware that the shortcut was helpful in the moment, but detrimental in the long term. I’d be curious to see how student responses would be different today; are students more willing to use it as their disillusionment with academia grows, or are they less willing now that there’s a substantial anti-AI backlash? I’ll be sure to report back after our next end-of-semester cocktail debrief.

Having just turned 30, I’ve naturally been doing a lot of reflecting. My college self, for whom writing was seen as little more than a necessary evil, would certainly be shocked to learn that I now write 2,000 words per week for fun. Then again, he’d probably be more shocked that I’m a woman. The only true constant in life is change.

Currently Reading

My friend Andy Gooding-Call is now a freelance media expert and photographer! Go hire him! https://andygoodingcall.com/

Fellow Substacker Jessica Slice has a new book out on disabled parenting, “Unfit Parent”! Go buy it now!

I was featured in a piece on how to reduce plastic use in the kitchen!

A radical computer scientist’s perspective on the real problems with AI (a great resource for your classrooms!)

On mutual aid.

Watch History

Required Viewing: Lily Alexandre’s must-watch new piece on how the trans community is rethinking visibility.

Three perspectives on visibility protests (my thoughts exactly!)

Taylor Lorenz’ definitive summary of how America normalized political violence.

A biologist making a Pokémon “tree of life” that’s surprisingly comprehensive!

This interview with Adele “Supreme” Williams about her new show, “OH MY GOD… YES!”

Bops, Vibes, & Jams

Ezra Furman’s new album “Goodbye Small Head” is trans folk excellence. Fav tracks: “Grand Mal”, “Power of the Moon”, “Slow Burn”.

CJ the X’s new EP “Sobermore” has the best production I’ve heard all year so far. Fav tracks: all of them.

Kali Uchis’ new English-language album “Sincerely,” is stunning as usual. Fav tracks: “Sugar! Honey! Love!”, “Silk Lingerie,”, and “All I Can Say”.

And now, your weekly Koko.

That’s all for now! See you next week with more sweet, sweet content.

In solidarity,

-Anna

Interestingly in college, I virtually never thought about getting a career. I was just enjoying the process of learning, and the first two years I took courses that looked interesting and challenging without even declaring a major. It ended up causing me some distress when I was forced to choose a major and realized I'd be cramming all the coursework into two years instead of four, but I still loved college anyway.

I very much appreciated this post. I also learned a great deal from your video. This week I’ve listened to AI Con and AI Snake Oil in an effort to understand what’s real and what’s not about super computing/LLMs, etc (since AI as a term is an umbrella and offers cohesiveness to a marketing concept). Your post and video were just in time.